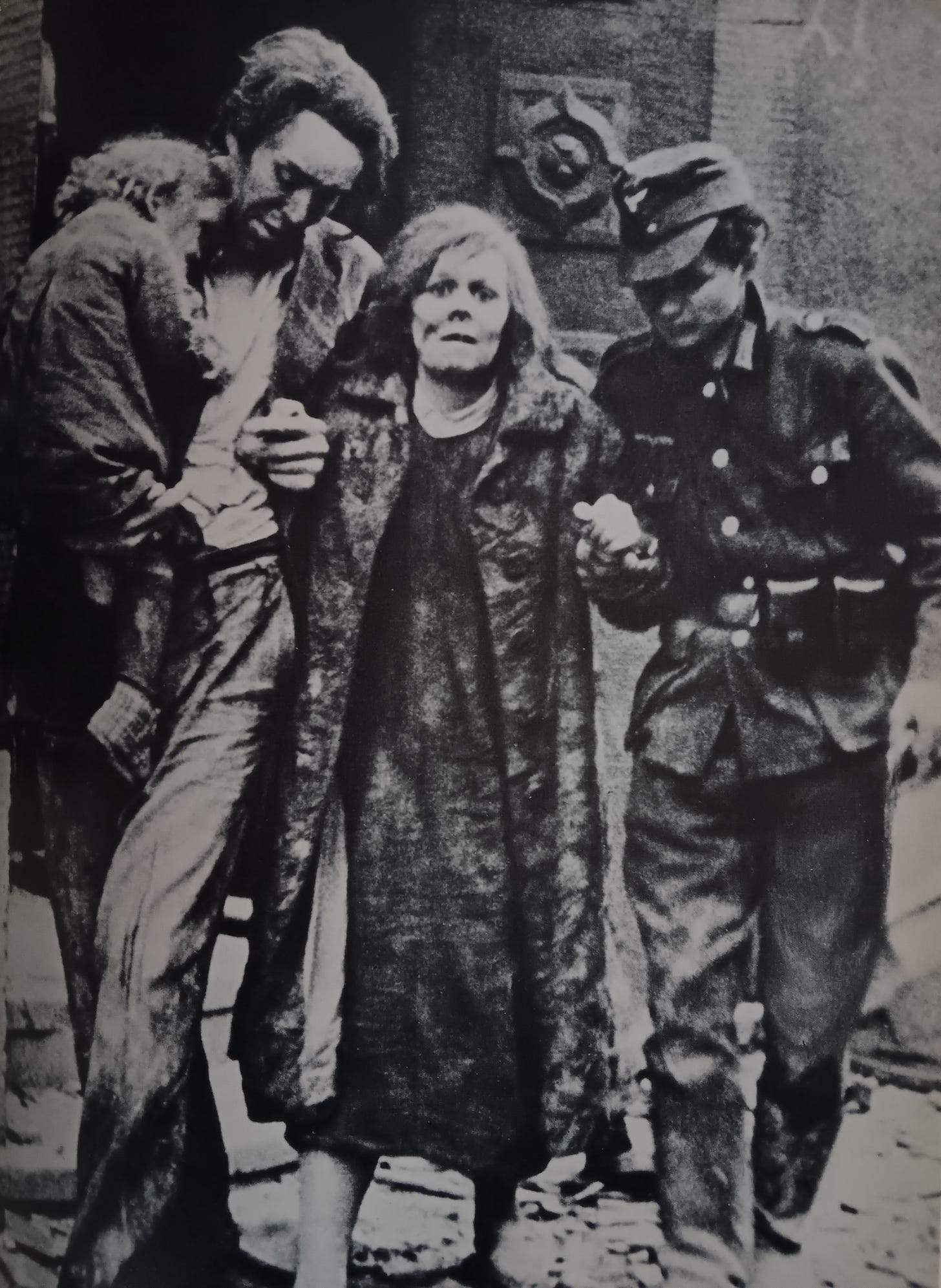

Chances are pretty good that you’ve never seen the picture above, or learned about the people in it. It’s a photograph of Germans in the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia in 1946. They are fleeing from horrendous anti-German violence that was occurring after World War II had ended. If you overlook the blonde children, you might think that it shows Jews being transported to concentration camps, but it’s a striking bit of evidence that the German people also suffered because of the war.

Germans had lived in the Sudetenland for many centuries. A largely German university was established in the city of Prague in 1348. German craftsmen, farmers, businessmen, aristocrats, civil servants, and scholars were well-established in the region for generations. Before World War I, the Sudetenland was part of the Habsburg empire. After that war, Sudeten Germans hoped, like other peoples, to follow a course of ethnic self-determination, encouraged by Allied leaders such as Woodrow Wilson. Many wished to join their territory with the adjacent Austria or Germany. Yet ultimately, the Allies did not allow these options. Czech troops occupied the region, and most of the Sudetenland was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. The rationale was for Czechoslovakia to have more ability to defend its borders. Approximately 3.3 million Germans constituted a substantial minority in that new nation. They, along with other minorities, suffered under language restrictions, censorship, and occasional violence.

The entire German nation and people were drastically affected by World War II, far beyond the terrible loss of military casualties. Before World War II, many ethnic Germans also lived in what is now Poland, the Baltic States, Hungary, Romania, the former Yugoslavia, and elsewhere. Austria, with a mostly German population, was incorporated into the German Reich in 1938. After World War II, Austria again became independent, and German borders were substantially changed in other ways. Sizeable regions such as East Prussia, Silesia, and most of Pomerania were taken by other nations. Germany thereby lost much of its agricultural land. Approximately 14 million Germans were forced to leave their homes, with around 2 million dying in the process. The situation turned especially bad for Germans in Czechoslovakia. Before and during the expulsions there, as writer Daniell Pfohringer stated, “There were indescribable atrocities that exceeded any imagination.” Many distressing reports by surviving eyewitnesses attest to this. Sometimes the Czech perpetrators used as an excuse, “A German is a German.” Intentional starvation was used as a weapon along with massive amounts of beatings, tortures, rapes, and murders. A shocking number of Germans committed suicide.

During World War II and its aftermath, Germans also suffered within what are now the borders of Germany. Approximately 5 million German military personnel and civilians died as a result of the war itself, although this figure is uncertain, and might be on the low side. Current estimates are that Allied bombing raids alone killed between half a million and 1 million civilians. Several hundred thousand German women were raped by Soviet soldiers, as the Red Army entered the country and then during the Soviet occupation of eastern Germany. Many of these women were raped repeatedly. Several military men and civilians were also murdered by the Soviets during the final days of the war and later. Destruction of cities, industries, bridges, railroads, and other facilities was widespread, caused by bombing, fighting on the ground, and Nazi scorched earth policies. Rape, homelessness, disease, malnutrition, looting, and general disorder continued to be severe after the German surrender, not only in the Soviet occupation zone, but also at times in the other parts of Germany and Austria that were occupied by the Americans, British, and French. Many women in the American zone felt that they needed to provide sexual favors to American servicemen in exchange for food and other necessities. German prisoners of war were held in bad conditions in the Soviet Union, with the last survivors arriving home in 1956. American economist Ralph Keeling described the fate of POWs and other German males who were taken to the USSR for forced labor: “The daily diet in Russian slave camps is soup and lectures on the glories of communism and the evils of western democracy. The slightest disobedience is penalized by such heavy work that a third of the culprits die within three weeks from exhaustion. A tenth of the slaves died during the first year, according to those who have returned.” On a smaller scale, many POWs were mistreated in some of the American and French-run camps, with men having to sleep out in the open in wet and cold conditions, and without enough food. None of this minimizes the terrible experiences of other peoples during the war, but German suffering has often been intentionally disregarded since 1945. Officials in Germany itself have tried to downplay it.

Envy is an extremely destructive emotion. Along with the desires for revenge and plain lawlessness, it played a large role in the attacks on Germans as the war came to an end. Soviet troops entering German territory were amazed and in some cases resentful at the prosperity which they saw, which was so different from conditions at home. Communist ideology encouraged hatred of people who were considered class enemies. Many prosperous Germans were singled out by Soviets and other enemies, and killed. Persons in certain professions were targeted for violent treatment. The Junkers, a class of aristocrats, were almost completely wiped out as a people. German journalist Margret Boveri could be very critical of powerful persons, yet she testified that “there were a good many decent sorts” among the Junkers. Some servants and farm workers stayed loyal to their Junker masters during the breakdown of Nazi Germany, and suffered violence too. Also, beautiful buildings were vandalized, plundered, and destroyed.

So, the German people paid a very heavy price during and immediately after the Second World War, for the sins that the Nazi Regime and some individual Germans committed, and for losing the war. Men, women, children, and the elderly suffered and died. Yet all of this was not enough for some of the Allies. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt acted upon fierce anti-German feeling which he had developed long before the war broke out. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, predisposed to be ruthless, led a country which had experienced awful devastation because of the German invasion. In the midst of the war, the top Allied leaders agreed to a demand that Germany must surrender unconditionally. A very harsh proposal for postwar Germany, revealed publicly during the war, was formulated by US Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau. This plan would have thoroughly deindustrialized Germany, and condemned it to impoverishment. It also would have required forced labor of Germans. Parts of the Morgenthau Plan were rightly rejected by Roosevelt’s successor Harry S. Truman during the occupation, but such Allied policies and proposals likely caused Germans to fight longer and harder than they otherwise would have. The insistence on unconditional surrender and other Allied intransigence also did not help the German resistance against Hitler, which included several military and civilian figures.

After the German surrender, the Allied occupiers ultimately implemented plans for Germany that were still punitive. Ralph Keeling argues that the results of the Potsdam Conference were especially harmful. The Potsdam summit meeting of Soviet, American, and British leaders, in July and August 1945, determined the “Political and Economic Principles to Govern the Treatment of Germany,” decisions about the postwar borders, policies of “denazification,” and other measures. In his book, Keeling showed that key terms such as “democracy” in the Potsdam decrees were poorly defined, leading to conflicting understandings of what the occupation should accomplish. One of the Potsdam principles was expressed in the following statement:

“German education shall be so controlled as completely to eliminate Nazi and militarist doctrines and to make possible the successful development of democratic ideas.”

As Keeling stated, though, “forbidding propagation and discussion of one political philosophy and forcing the public to accept a different one held by those in the seats of power is Nazi doctrine. It is also Communist doctrine. And the Communists claim theirs is the one and only genuine democracy…. Political democracy, say the Bolsheviks, is impossible over the long run without ‘economic democracy,’ by which they mean abolition of private ownership of property, the foundation of free enterprise. But they call free enterprise fascism, and defenders of the American system fascists. And Nazism is a form of fascism. Denazification, in Russian eyes, therefore, is tantamount to rooting out our own system, along with all other private property systems….”

Keeling also made an ominous prediction, which we saw come true in recent years: “By continuing to condemn the defeated in this war as a race of criminals and punishing them accordingly, as we at first set out to do, we would be setting a most dangerous precedent, one which our children might have good reason to regret.”

Some of the denazification procedures were reasonable and probably necessary to recreate a stable, peaceful society, by removing committed Nazis from powerful positions and bringing war criminals to justice. Yet, along with the damaging restrictions on freedom of thought, denazification also caused major disarray when skilled Germans, who were not fanatical Nazis, were nevertheless prevented from working productively. Those who administered and implemented denazification—the “purge machinery,” as Keeling called it—included many Communists and Socialists. Denazification was probably the harshest in the American zone of occupation.

And daily life for most Germans remained very hard, long after the surrender. Food rations were sometimes intentionally kept very meagre, while private assistance from charities was, for a time, blocked or hindered. Over 3000 German factories were dismantled after the war and removed to the Soviet Union. The other Allies also took significant amounts of industrial equipment. German scientists and other specialists were forcibly or voluntarily removed to work for the victorious nations. Major reparations were also required by the Potsdam decisions. And in the Soviet zone, Germans lost their private property via a system of “Communization,” along with high inflation that was caused by the Soviet authorities. These policies prolonged the extreme destitution that was experienced in Germany.

Some occupation authorities tried conscientiously to assist the Germans. American military governor Lucius Clay was an example. Not only were these officials sometimes hampered by occupation policies, but worldwide food shortages and transportation difficulties complicated the situation. Food imports from America finally helped relieve the dire nutrition problem. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill also tried to moderate or halt retribution by Allied officials against the Germans. While he favored some deindustrialization, he opposed severe reparations, and wanted to ensure security for German workers. He had stated in 1944 regarding Germany, “You cannot indict a whole nation.” And he seems to have meant it. When Stalin and Roosevelt lightly proposed executing around 50,000 German officers, Churchill was outraged, whether the proposal was in jest or not. On August 16, 1945, after he had lost his position as Prime Minister, Churchill stated in the House of Commons:

“I am particularly concerned, at this moment, with the reports reaching us of the conditions under which the expulsion and exodus of Germans from the new Poland are being carried out. Between 8,000,000 and 9,000,000 persons dwelt in those regions before the war. The Polish Government say that there are still 1,500,000 of these not yet expelled within their new frontiers. Other millions must have taken refuge behind the British and American lines, thus increasing the food stringency in our sector. But enormous numbers are utterly unaccounted for. Where are they gone, and what has been their fate? The same conditions may reproduce themselves in a more modified form in the expulsion of great numbers of Sudeten and other Germans from Czechoslovakia. Sparse and guarded accounts of what has happened and is happening have filtered through, but it is not impossible that tragedy on a prodigious scale is unfolding itself behind the iron curtain which at the moment divides Europe in twain.”

The British occupation was relatively mild compared with that of the Americans, Soviets, and French. Amidst the devastation, here and there, in the last days of the Nazi regime and under Allied occupation, some individual Russians, Americans, Britons, Poles, Czechs, and Frenchmen did what they could for Germans. Eventually, with currency reform, the Marshall Plan, and other positive measures, stability and prosperity returned to the regions of Germany which had been occupied by the Western powers. America also had an interest in preserving the well-being of West Germany with the development of the Cold War.

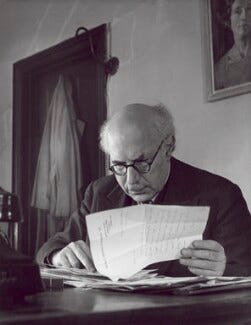

Many of us believe that “two wrongs don’t make a right.” Soon after World War II, the Jewish leftist publisher Victor Gollancz was troubled by his conscience about how the Allies were treating defeated Germany. In 1946, Gollancz traveled from his British home to Germany, where he witnessed the severe malnutrition, infant mortality, and impoverishment. He stated, “nothing can save the world but a general act of repentance in place of the present self-righteous insistence on the wickedness of others, for we have all sinned, and continue to sin most horribly.” This seems like something that all of us should remember, whether we are left or right or neither.

Christian morality forbids not only many acts which Nazis committed, but also acts which were perpetrated against countless Germans. Clearly, some Allies during and after the war attempted to abide by Christian principles as best they could. Others sought revenge, or plainly just opportunities to hurt others, wreak havoc, and gain personal or group advantage. Some of the revenge was understandable, but much of it demonstrated why the Bible teaches that vengeance belongs to God. Roman Catholic Archbishop Josef Frings of Cologne, Germany, who had openly opposed the Nazis and had been attacked by them, stated in a Christmas 1945 message, “I have always made it plain that the whole nation is not guilty, and that many thousand children, old people and mothers are wholly innocent and it is they who now bear the brunt of the suffering in this general misery.”

The Allies had some justification in going to war with Germany, but some moral issues of the conflict, its origins, and its aftermath are more complicated or different than what we have been led to believe. The Nazi regime committed great crimes, especially against Jews, Slavs, political opponents, foreign laborers, and persons who were considered unfit and who were euthanized. Many Germans did not participate in such acts, though. Some Germans were unaware of the atrocities. Many German soldiers, sailors, and airmen believed that they were doing their patriotic duty, and rejected terrible acts committed by their regime, and many continually tried to do the right thing. Some committed atrocities. Some didn’t. And all Germans were trapped under a regime that constantly threatened dissent with imprisonment, torture, and death.

These realities once were understood by some in the West. For a few decades, postwar histories and some elements of popular culture emphasized that there were always decent Germans. This was reflected in popular movies such as “The Great Escape” (1963). From World War II onwards, though, some politicians, media figures and church leaders insisted that Germans should be considered collectively guilty. These accusations, combined with some of the harsher techniques of denazification, seem to have contributed along with other ideological factors to the oppressive leftist political practices that we currently see throughout the West. After the war, an extreme antifascist political movement gained power and influence in various institutions and academic departments, and sometimes resulted in the falsification and distortion of history. Paul Gottfried aptly describes this postwar antifascism as having an “increasingly frenetic nature.” Concurrently, Political Correctness and Woke became dominant in much of the West, and, as Gottfried wrote, “German reeducation has become a model for the reconstruction of other Western societies.” Combined with this, “the working masses are viewed as the bearers of deep-seated fascist and authoritarian attitudes.” Books such as The Authoritarian Personality, in 1950, argued that the traditional western family provided a basis for fascist oppression. The traditional western family has been under relentless assault ever since.

Together these arguments and developments have grown to the extent that some people, within and outside Germany, view all Germans of the past as intrinsically evil, and believe that Germanness must be continually punished, and even eradicated. Of course, similar ideas are also applied against other western peoples. Eradication of the German people is actually proceeding, with the encouragement of low birth rates, the welcoming of overwhelming numbers of non-German migrants, and relentless media messages of collective German guilt. In and outside Germany, governments tolerate violent Antifa groups. The widely promoted meme of “Punch a Nazi” indicates that physical violence is considered acceptable against some political opponents—often anyone who is to the right of what once was the political center. Even traditional Americans who are Trump supporters, and who fervently believe in the American Constitution, are regularly denounced as fascists and Nazis. Such epithets, along with “far-right,” are frequently used by globalists and their followers in contexts in which actual threats by far-right persons are miniscule or nonexistent.

There was no reasonable justification for the atrocities committed against Germans when the war was ending and in the following years. The process of population transfers should and could have been done in a much more humane way. Judicial processes could have been more carefully followed, to punish those who were guilty of war crimes. German women did not deserve to be raped. Children, old people, disarmed POWs, and others did not deserve to be murdered. And punitive economic practices and looting were wrong. On the Allied side, not only did some individuals and groups act criminally in the chaos of the last months of World War II, but some politicians, officials and ideologues acted shamefully also, cold-bloodedly. And even in recent decades, Germans have been discouraged from mourning the great losses which they suffered. Finally, all of us in the West have suffered under ideologies which were jump-started against the postwar Germans.

The American Ralph Keeling says it well:

“We thought we were coming to Germany as liberators to free the German people from dictatorship, to teach them the errors of their ways, and to give them the benefits of our form of democracy and free enterprise. Actually we accepted at Potsdam a program which negated all of our principles... The Potsdam plan was made to order for Soviet Russia, but not for free enterprise or free democratic processes. Its very execution requires totalitarianism of the kind the Soviets are accustomed to, of the kind which, when the Nazis were practicing it, so outraged us that we fought a half trillion dollar war to eradicate it from the earth.

We first eliminated the German government, the only instrumentality through which the German people might take collective self-preservative action and then substituted a system of military absolutism, born not of free American institutions or ideals, but of the absolutisms dominant at Potsdam…. This dictatorship, as we have seen, had as its purpose not the resuscitation and rehabilitation of the fallen Reich, but rather its repression and the erection of barriers to recovery….”

The seeds of repression that were planted at Potsdam were also carried and planted throughout other Western countries. They were mingled with other anti-Western seeds. And their evil, destructive, ugly flowers bloomed in Germany, and then elsewhere.

References

Beevor, Antony, The Fall of Berlin, New York: Viking, 2002

Bernhardt, Gero, “The Terrible Fate of the Sudeten Germans,” Compact Magazine, Oct. 5, 2024 (original in German), https://www.compact-online.de/das-furchtbare-schicksal-der-sudetendeutschen/

Gilbert, Martin, Churchill: A Life, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1991

Gottfried, Paul, Antifascism: The Course of a Crusade, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2021

Hansard, “Debate on the Address,” 16 August 1945, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1945/aug/16/debate-on-the-address

Joint Report with Allied Leaders on the Potsdam Conference, August 2, 1945, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/91/joint-report-allied-leaders-potsdam-conference

Keeling, Ralph Franklin, Gruesome Harvest, Chicago: Institute of American Economics, 1947

Knowles, Christopher, “How It Really Was: Victor Gollancz - In Darkest Germany,” October 28, 2005, https://howitreallywas.typepad.com/how_it_really_was/2005/10/victor_gollancz.html

McDonogh, Giles, After the Reich: The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation, New York: Basic Books, 2007

McMeekin, Sean, To Overthrow the World: The Rise & Fall & Rise of Communism, New York: Basic Books, 2024

Pfohringer, Daniell, “Unforgotten: The Old German East,” Compact Magazine, Oct. 8, 2024 (original in German), https://www.compact-online.de/unvergessen-der-alte-deutsche-osten/

Turnwald, Dr. Wilhelm, Documents on the Expulsion of the Sudeten Germans, Study Group for the Preservation of Sudeten German Interests, 1951, https://www.wintersonnenwende.com/scriptorium/english/archives/whitebook/desg00.html